OPINION

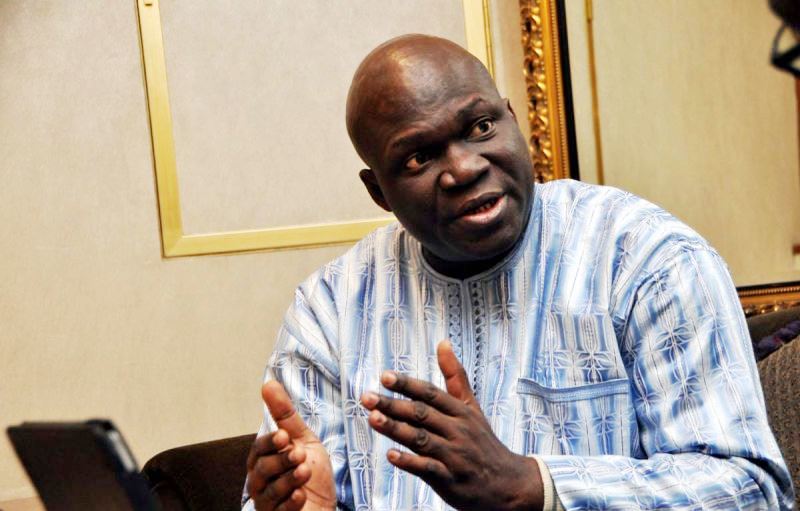

Who governs Nigeria? By Reuben Abati

During the Jonathan administration, an outspoken opposition spokesperson had argued that Nigeria was on auto-pilot, a phrase that was gleefully even if ignorantly echoed by an excitable opposition crowd. Deeper reflection should have made it clear even to the unthinking that there is no way any country can ever be on auto-pilot, for there are many levels of governance, all working together and cross-influencing each other to determine the structure of inputs and outcomes in society. To say that a country is on auto-pilot is to assume wrongly that the only centre of governance that exists is the official corridor, whereas governance is far more complex. The question should be asked, now as then: who is governing Nigeria? Who is running the country? Why do we blame government alone for our woes, whereas we share a collective responsibility, and some of the worst violators of the public space are not even in public office?

The President of the country is easily the target of every criticism. This is perhaps understandable to the extent that what we have in Nigeria is the perfect equivalent of an Imperial Presidency. Whoever is President of Nigeria wields the powers of life and death, depending on how he uses those enormous powers attached to his office by the Constitution, convention and expectations. Nigeria’s President not only governs, he rules. The kind of President that emerges at any particular time can determine the fortunes of the country. It helps if the President is driven by a commitment to make a difference, but the challenge is that every President invariably becomes a prisoner.

He has the loneliest job in the land, because he is soon taken hostage by officials and various interests, struggling to exercise aspects of Presidential power vicariously. And these officials do it right to the minutest detail: they are the ones who tell the President that he is best thing ever since the invention of toothpaste. They are the ones who will convince him as to every little detail of governance: who to meet, where to travel to, and who to suspect or suspend. The President exercises power, the officials and the partisans in the corridors exercise influence. But when things go wrong, it is the President that gets the blame. He is reminded that the buck stops at his desk.

We should begin to worry about these dangerous officials in the system, particularly within the public service, the reckless mind readers who exploit the system for their own ends, and who walk free when the President gets all the blame. To govern properly, every government not only needs a good man at the top, but good officials who will serve the country. We are not there yet. The same civil servants who superintended over the omissions of the past 16 years are the ones still going up and down today, and it is why something has changed but nothing has changed. The reality is terrifying.

The officials at the state levels are no different, from the Governor down to the local government chairman and their staff. They hardly get as much criticism as the folks in Abuja, but they are busy every day governing Nigeria, and doing so very badly too. Local government chairmen and their officials do almost nothing. The Governors also try to act as if they are Imperial Majesties. The emphasis on ceremony rather than actual performance is the bane of governance in Nigeria. Every one seems to be obsessed with ceremony and privileges.

A friend sent me a picture he took with the Mayor of London inside a train, in the midst of ordinary citizens and asked if that would ever happen in Nigeria. The Mayor had no bodyguards. He was on his own. In the Netherlands, the Prime Minister is a part-time lecturer in one of the local colleges. Nigerian pubic officials are often too busy to have time for normal life. Even if they want to live normally, the system also makes it impossible. We need people in government living normal lives. Leaders need not be afraid of the people they govern. They must identify with them. There is too much royalty in government circles in Nigeria. No matter how well-intentioned you may be, once you find yourself in their midst, you will soon start acting and sounding like one, because it is the only language that is spoken in those corridors.

Elsewhere, ideas govern countries. People become leaders on the basis of ideas and they govern with ideas. That is why the average voter in Europe or North America knows that what he votes for is what he is likely to get. Clearly in the on-going Presidential nomination process in the United States, every voter knows the difference between Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton on the Democratic side and between Ted Cruz and Donald Trump on the Republican side. Such differences are often blurry in Nigeria: our politics is driven by partisan interests; a primordial desperation for power, not ideas. It is also why Nigerian politicians can belong to five different political parties and movements within a decade.

Even when men of ideas show up in the political arena, they are quickly reminded that they are not politicians and do not understand politics. Gross anti-intellectualism is a major problem that Nigeria would have to address at some stage. Some of the administrations in the past who had brainy men and women of ideas in strategic positions ended up not using them. They were either frustrated, caged, co-opted or forced to adapt or shown the door. The question is often asked: why don’t such people walk away? The answer that is well known in official corridors is this: doing so may be a form of suicide. Once inside, you are not allowed to walk out on the Federal Government of Nigeria, and if you must, not on your own terms. So, governance fails even at that level of values: that other important element that governs progressive nations.

Partisan interests are major factors in the governance process. These seem to be the dominant factor in Nigeria, but again, they are irresponsibly deployed. The crowd of political parties, religious groups, traditional rulers, ethnic and community associations, professional associations, pastors, priests, traditional rulers, imams and alfas, shamanists, native doctors, soothsayers and traditional healers: they all govern. They wield enormous influence. But they have never helped Nigeria and they are not helping. All the people in public offices have strong links to all these other governors of Nigeria, but what kind of morality do they discuss? Those with partisan interests, including even promoters of Non-Governmental groups (NGOs) all have one interest at heart: power and relevance.

The same priests who saw grand visions for the PDP and its members over a 16-year period are still in business seeing visions and making predictions. Those who claim to be so powerful they can make the lame walk and the blind see have not deemed it necessary to step forward to help the NNPC turn water into petrol. If any of these miracle-delivering pastors can just turn the Lagos Lagoon alone into a river of petrol, all Nigerians will become believers, but that won’t happen because they are committed to a different version of the gospel. As for the political parties: they are all in disarray.

The private sector also governs Nigeria. But what is the quality of governance in the corporate sector? The Nigerian corporate elite is arrogant. They claim that they create jobs so the country may prosper, but they are, in reality, a rent-seeking class. They survive on government patronage, access to the Villa and its satellites, and claims of indispensability. But without government, most private sector organizations will be in distress. The withdrawal of public funds into a Treasury Single Account is a case in point. And with President Muhammadu Buhari not readily available to the eye-service wing of the Nigerian private sector, former sycophants in the corridors are clandestinely resorting to sabotage and blackmail. A responsible private sector has a duty in society: to build society, not to donate money to politicians during elections and seek patronage thereafter. And if it must co-operate with government, it must be for much nobler reasons in the public interest.

The military are still governing Nigeria too. They may be in the background, but their exit 16 years ago, has not quite translated into a loss of influence or presence. In the early years of their de-centering, many of them chose to join politics and replace their uniforms with traditional attires. Their original argument is that if other professionals can join politics, then a soldier should not be excluded. They failed to add that the military class in politics in Africa has shown a tendency to exercise proprietorial rights and powers, which delimit the democratic project. In Nigeria such powers and rights have been exercised consistently and mostly by, happily for us, a gerontocratic class, whose impact, I believe, will be determined by the effluxion of time.

And it is like this: the President that emerged in 1999 was a soldier: the received opinion was that only such a strong man could stabilize the country. His successor was the brother of another old soldier; he and his Deputy were personal chosen by the departing President. He died in office, but for his Deputy to succeed him, it helped a lot that he was also a favourite of the General who chose his own successors. When this protégé fell out with the General, in retrospect now, a miscalculation, the General turned Godfather swore to remove him from office. And it happened. In 2015, another former soldier and strong man, had to be brought back to office and power. When anything goes wrong, a class of old Generals are the ones who step forward to protect and guide the country. The only saving grace is that they do not yet have a successor–class of similarly influential men with military pedigree. But when their time passes, would there be equally strong civilians who can act as protectors of the nation?

The media governs too. But the media in Nigeria today is heavily politicized, compromised and a victim of internal censorship occasioned by hubris. Can the media still save Nigeria? It is in the same pit as the Nigerian voter, foreign interests, the legislature and the judiciary. But when there is positive change at all of these centres of power and influence, only then will there be change, movement and motion, and a new Nigeria.

Davido's Net Worth & Lifestyle

Davido's Net Worth & Lifestyle