OPINION

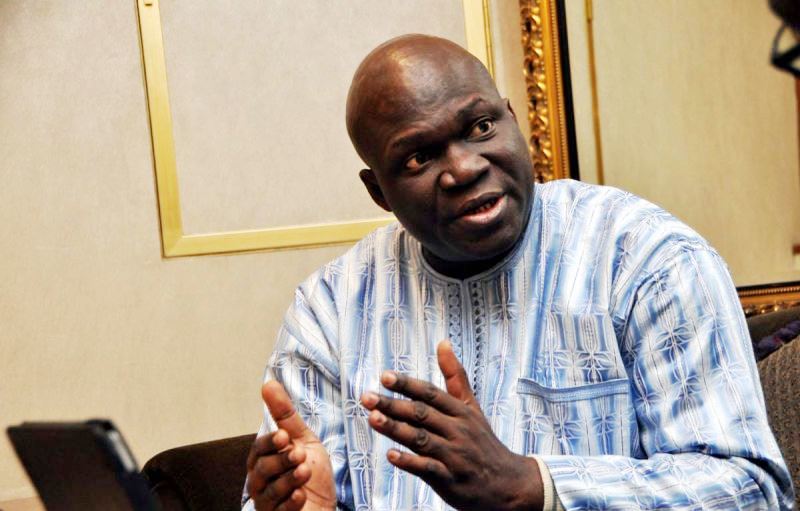

Reuben Abati: Where is the Nigerian opposition?

Less than a year to the next general elections in Nigeria, the biggest deficit in the political process leading to that moment is the absence of a robust, virile and effective opposition. The role of the opposition in a democracy is to question, criticize, challenge, and audit the governments of the day – local and national – and make them more transparent and accountable, and even if these twin-objectives may not be immediately achieved, the opposition exists nonetheless to put the people in power “on their toes” as it were in the people’s overall interest.

This is the underlying principle of a parliamentary system of government, and even in other forms of government including a Presidential system, the opposition provides checks and balances, it is a kind of alternative government, a counterweight, providing such balance that could safeguard the integrity of the political process. But of course, what is at stake is “the conquest of power”: the opposition provides the people with a choice and ultimately seeks to wrestle power from or out of the hands of the incumbent and present a different vision of social and economic progress.

In doing this, the opposition may be constructive – in this regard it could even work with the ruling party or government to promote the national interest. This was the case under Prime Minister Narasimha Rao of India who once sent opposition leader Atal Bihari Vajpayee to the United Nations Human Rights Commission in Geneva, as leader of the Indian delegation, to defend the government on its human rights record in response to allegations by Pakistan.

Rao’s party members, who felt he had no business working with the opposition criticized him as loudly as they could, but the Prime Minister felt it was more important to be bi-partisan and project a picture of national unity. It is not a strategy that has endured in India’s divisive politics. But what is known is that in other jurisdictions, members of the opposition in parliament sometimes vote on a non-partisan basis on key issues before the parliament. This may occur when the rivalry among the political parties is peaceful and there is a broad consensus that the country is far more important than the boundaries imposed by partisan politics.

For the most part however, opposition politics can be disruptive, and apropos, the strategy of the opposition is not to construct anything or offer any value but to “oppose, oppose, oppose” by any means possible to wear down and pull down the incumbent government. Physical violence, blackmail, abusive words, post-truth imagery and fake news are part of the arsenal of the disruptive opposition.

In Nigeria at the moment, we neither have in my estimation a constructive or a disruptive opposition. Whatever we have that may look remotely as any form of opposition is weak, uncoordinated, and ineffective. Our political parties are internally polarized, politics has become evil, our political leaders do not know where to draw the line, the ruling government is having an upper hand, it is committed to an unrelenting, overzealous persecution of the opposition and progressive ideas. The last time we witnessed what looked like organized opposition, even if it was disruptive, was ironically through the All Progressives Congress (APC). In 2013, a number of political parties formed a synergy with civil society groups to become the All Progressives Congress, and adopting an “oppose, oppose, oppose” strategy, they managed by 2015 to get the ruling Peoples Democratic Party out of power. It was a major turning point in Nigerian politics since the return to civilian rule in 1999.

But the PDP was not prepared for its new role as the leading opposition party, just as the new government led by the APC was equally unprepared for governance. This sudden reversal of roles caught Nigeria’s main political actors napping. The APC at the centre found it difficult to even appoint Ministers: it took six months to come up with a list. In one or two states, the Governors acted as sole administrators for up to a year. There are about 80 registered political parties in the country, but these are at best relatively unknown parties.

The main political party, the PDP has been largely in disarray since it lost power. Most of its members have defected to the new ruling party, many of its founding fathers now prefer to be known and addressed as statesmen, and the party’s strong mouthpieces have all been cowed into silence by a ruling party that is wielding power like a whip. The PDP came out of power mired in a corrosive in-fighting and blame-sharing that robbed the party of its soul. It was later “kidnapped”, and then rescued, but it is not yet in strong enough shape to stand up to the ruling party, offer alternative views or organize itself properly. Who is even the national leader of the PDP? Close to the next general elections as we are, nobody is quite sure. What exactly does the PDP want to do? It is not so clear either. Is the PDP still interested in power? If it is, it is not showing the kind of determination that the APC projected in 2014.

There are PDP members in the legislature at the Federal and State levels, but their voices have not been loud enough. Nigerian politics has not been ideology-driven for a while, that is one explanation, but it is also possible that the remaining PDP members are hedging their bets and secretly planning to join the APC. This is the case because the ruling APC is now in charge of state resources – and that is a major attraction for Nigerian politicians, besides, the APC not knowing how to govern has been functioning more as an opposition party. It has spent the last three years hounding PDP members and the Jonathan administration, and making it difficult for anyone to come up with progressive, opposition ideas.

It had to take Microsoft’s Bill Gates to criticize the Economic Recovery and Growth Programme (ERGP) of the Federal Government before the PDP realized that such a document existed. The new PDP, failing in its role as an opposition party, cedes the initiative to the APC and merely reacts through statements that do not even make much impact. In the states across the Federation, opposition members often forget what their role in the legislature is supposed to be as they join the queue of lawmakers trooping to the Government House to collect favours from imperial Governors. At the Federal level, APC Senator Dino Melaye has functioned more as an opposition leader than any PDP Senator with his persistent interrogation of Executive policies and actions. One or two PDP Senators, along with some other APC members, in comparison, have since acquired a reputation for going to the Red Chamber to sleep during plenary sessions! There is no quality debate as such in our parliaments, more or less, and so the debate about Nigeria has shifted to morning shows on radio and television, oftentimes conducted by ill-equipped analysts and the hysterical crowd.

It is the country that pays the cost when the opposition is asleep, and one political party is allowed to ride roughshod over everyone just because it is in power and office. When members of the APC claim that there is no alternative to President Muhammadu Buhari, I guess they are not saying there are no persons who are better qualified than the President; rather they are saying they cannot see any organized opposition that could pose a threat to the continued stay of the Buhari government in power beyond May 2019. And by conduct, they even make it clear that whoever challenges the APC should be prepared to face the consequences of doing so. The APC mastered bully tactics as an opposition party. It continues to rely on the same tactics as a ruling party.

The gap that has been created by the absence of an effective opposition in Nigerian politics since 2015 is gradually now being filled by thought leaders. Sometime in 2016, I wrote a piece titled “Where are the public intellectuals? in which I challenged the Nigerian intelligentsia generally to rouse from its slumber. That slumber is perhaps understandable. The Nigerian intelligentsia bought into the APC project in 2014 and 2015, and wanted the PDP out of the way by all means. Not too long ago, confronted with the failings of the APC as a ruling party, this special class has since recanted. I dealt with that in “The season of recanting” (Jan.16) but since this other article, the political space has since become more interesting with the interventions of persons like Chief Olusegun Obasanjo, General Ibrahim Babangida, General TY Danjuma, Professor Wole Soyinka and the emergence of groups like the Obasanjo-led Coalition for Nigeria, the Agbakoba-led Nigeria Intervention Movement (NIM), the Ezekwesili-led Red Card Movement, and the Concerned Nigerians Movement led by Charly Boy Oputa. The main battle-ground in recent times however has been the Nigerian social media where young Nigerians have been quite loud in expressing their dissatisfaction with the Buhari administration. The social media proved to be a strong weapon of mobilization in the hands of the APC before 2015, now it is its main nemesis.

Useful as these interventions, this reawakening of the civil society, may seem, the value is limited except there is a formal opposition that is specifically organized for the “conquest of power” at the polls. There is a growing consensus among these groups that both the APC and the PDP are of no use, they have not yet identified an alternative political party that can engage the ruling party but I believe the point is not lost on the actors involved that elections are won or lost not on twitter but by political parties actively organized for political action. Opposition politics involves branding, strategy, organization and pro-active action. Nigerian Opposition parties seeking to dislodge the APC can work together to form a political coalition as the APC did in 2013, and even if they do not win in 2019, the country’s political process would be better enriched by a constructive and strong engagement from the opposition that any ruling government deserves.

The current infidelity of the average Nigerian politician is the biggest obstacle that I see. Most Nigerian politicians do not necessarily go into politics because of what they can contribute, but because of what they intend to take out of it. The APC would continue to insist on its self-ascribed invincibility if the best that other political parties can offer is to apologize. The PDP Chairman recently apologized to Nigerians for whatever the PDP did while in power for 16 years. I don’t know whether that is meant to be a strategy or a confession but the meaninglessness of it has been exposed by the vicious responses from the APC and how the PDP has found itself having to struggle to put in a word. The Nigerian Opposition when eventually it awakens and seeks to engage the APC must realize that the APC has a tested opposition machinery, which found itself out of depths in the context of governance, but which in an election season could assume its emotional memory state, and with the resources now at its disposal, including power, prove to be deadly.

Opposition politics is not rocket science and nobody has to travel to India, the UK or the United States to master it. In Nigeria’s First and Second Republics, whatever may have been the problems of that era, this country had a rich culture of opposition politics. Chief Obafemi Awolowo of the Action Group and later the Unity Party of Nigeria, as an opposition leader, confronted the ruling government with hard facts and figures and an alternative vision of how Nigeria could be rescued. Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe, Malam Aminu Kano and Alhaji Ibrahim Waziri – opposition figures at various times – also stood for something. Whoever wants to rule Nigeria or any part thereof should be prepared to tell us exactly what he or she wants to do and how and when. If we have not learnt any lesson, we should by now have realized that a politician wearing Nigerian clothes, taking fine photos, eating corn by the roadside, over-promising, pretending to respect women and children, distributing cash and food, claiming to be a democrat, dancing to impress, and sometimes projecting himself or herself as nationalistic may not be what we are made to see. Nigeria needs a different breed, new faces, new ideas, a new way of politics.

Davido's Net Worth & Lifestyle

Davido's Net Worth & Lifestyle